In the Western media there is practically no more talk about Kherson Oblast. After the Novaya Kakhovka Dam was bombed by Ukraine, which Ukraine has as expected denied, and water from the Dnepr reservoir flooded the entire territory downstream, including many civilian settlements.

Western media immediately launched into accusing Russia of blowing up the dam to prevent the Ukrainian “major counteroffensive” in the Kherson region. Too bad that the flooding downstream of the dam also touched several Russian positions, which were then set back. All this without considering that the Ukrainian “great counteroffensive” of 2023 failed miserably despite the great publicity given in the West and all the resources that from Europe and the U.S. came to Ukraine.

But what does the Kherson region look like today and how do the towns on the Russian side of the Dnepr River live? I had never seen the Kherson oblast before, it was the only one of the new Russian territories I had not yet reached, so my curiosity was high.

The first center I visit is Genichesk, the provisional administrative center of the region. A charming seaside resort, a classic Russian coastal town with low-rise houses and lots of tourist potential. It all seems very quiet, but one only has to talk a little with the residents to understand that here, as in Zaporozhye the main problem is the drones.

And how better to understand the situation than by visiting what are the settlements along the river? Kakhovka, Novaya Khakovka and Aleshky, across from Kherson. The first settlement I reach after a couple of hours’ drive is Kakhovka itself. I manage to arrive right on the bank of the Dnepr, on the city’s riverfront, when I am stopped by barbed wire and a very very clear sign: “mines.”

Three or four kilometers separate me from the other bank, which is controlled by the Ukrainian army. In the town there are very few people walking around in the street, even though the stores are open. People know that walking around in the street means exposing themselves to the risk of drones and artillery, which is constantly hitting civilian buildings, houses, here. Military targets in the city there are none, as the military is in positions, further ahead of the city. I arrive at the local hospital. A short time ago a vampire missile, one of the Western missiles supplied to Ukraine to defend “democracy and freedom,” came right over the hospital in Kakhovka, a hospital that serves the civilian population of the city, not a military hospital.

An hour before I arrived in the city a kamikaze drone had hit an auto repair shop, I reach it. What the drone hit is a simple car repair shop. Nothing military, just civilian cars and civilian workers going about their work.

The drone came into the yard and destroyed all the parked cars. Thank God no one was injured because no workers were working outside at that time. On the ground in addition to the debris is still gasoline spilled from one of the tanks, which could have ignited and caused a serious fire that could have attacked other structures besides this bombed-out workshop. The investigative committee has already collected the necessary findings to catalog and document this umpteenth Ukrainian attack on civilians. The same civilians that Ukraine claims in its propaganda for the West to want to liberate from “Russian occupation.”.

I get back in the car and drive to the center of Novaya Kakhovka, the town that houses the dam and its hydroelectric plant. Here the town is truly deserted. Everyone is locked inside their homes, especially those who live near the river bank. The danger from the drones is tangible. I interview a local town official, Anna Polonskaya, and she tells me that being on the street is very dangerous, that the town is constantly attacked by Ukrainian drones and mortars that, she says verbatim, “fire on houses.”

Anna repeats, “there are no military targets here, the military is in its positions.”

But evidently the Ukrainian military doesn’t care about that. I climb a building to be able to film and photograph the dam, but I have to be very careful, I have to stay covered because on the other side of the Dnepr the Ukrainian snipers are always at work, and few things would make them happier than to shoot at a journalist who is working on the Russian side of the front. The dam is there, damaged. The river now flows unimpeded. The sounds of artillery, however, are constant. Can’t stay long here, I get out and head back toward the car. On our way back, together with the colleague I arrived with, we hear a buzzing “Drone!”; immediate reflection, we have to hide under the trees or in the first building, away from the road. A couple of minutes pass like this, in silence, where we hear only the sound of rain and try to listen if the drone is still in the air.

Once we reach the car we set off at full speed, the area is hot and it is time to get away quickly. We head for the town of Aleshki, on the left bank of the Dnepr. Opposite is the town of Kherson, which Ukraine recaptured in late 2022.

The situation here is much more tense than in the other cities. As we arrive, on the road, we constantly see the wreckage of cars hit by Ukrainian kamikaze drones, along with craters dug by artillery shells. As we approach the town, Alexander, who is driving, tells me there is a drone behind us. Immediately we accelerate and turn into the small streets on the outskirts of town. In these cases some tricks can save your life; run faster than the drone, which has a limited range and therefore might decide to change targets, enter a tree-lined avenue or a narrow street between buildings, so that the drone has difficulty following the target. We get lucky and after a few meters it seems that the drone has given up on us. We quickly hide the car in some kind of abandoned garage and start walking around the city. Here I cannot wear any protection, no green clothing. I must avoid in any way being mistaken for a soldier or a journalist. I cannot use a camera, only my phone. Soldier or journalist makes no difference to Ukrainians: you are an enemy.

In Aleshki there is total silence, interrupted only by explosions, more and less distant. Sometimes, for a few minutes, you can even hear birds. When you pass by some inhabited houses, which is quite rare, you can hear the sound of generators.

For there is no electricity here, and those who are left have adapted to living with generators. Not a single structure is intact. The Ukrainian armed forces have managed to really hit every structure that might have social value. Pharmacies, stores, clinics, offices, grocery stores. There is nothing usable. Even the park, where there is a small memorial to the Great Patriotic War, which miraculously survived Kiev’s post-2014 “decommunitization” effort, was damaged by Ukrainian artillery.

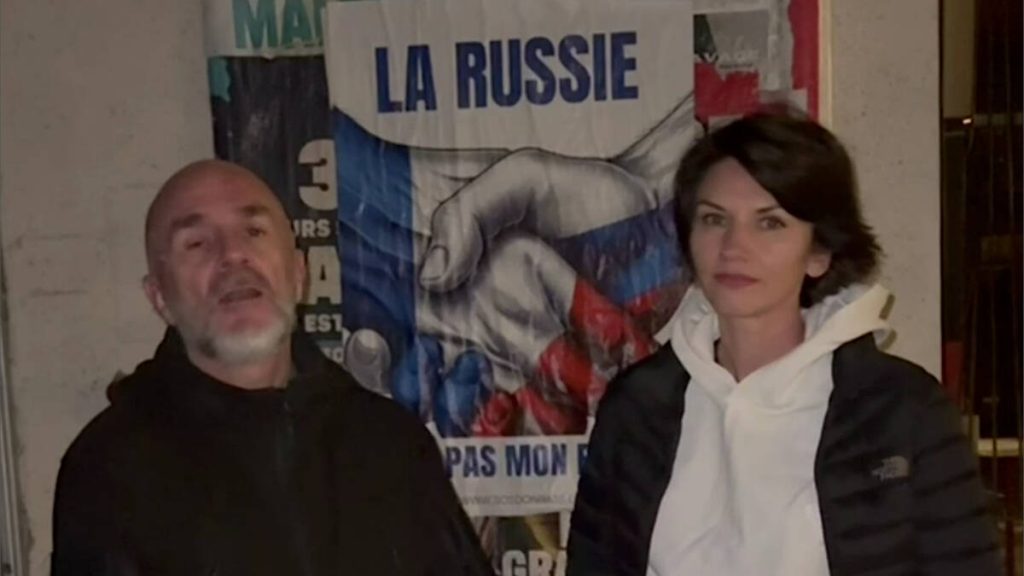

As I walk back I wonder why so little is said about this region in the West. Perhaps for the Western press to report what is happening here, with mortar shells and drones on houses, is not very convenient. It would undermine the constant narrative of Kiev, which even these days does nothing but demand arms and money from Europe and the United States. But fortunately, I am not alone here; there are many Western journalists who are ready to tell a different perspective on the conflict in the hope of being able to tear through the veil that has been very insistently trying to hide the reality of what is happening here for years.

Andrea Luccidi