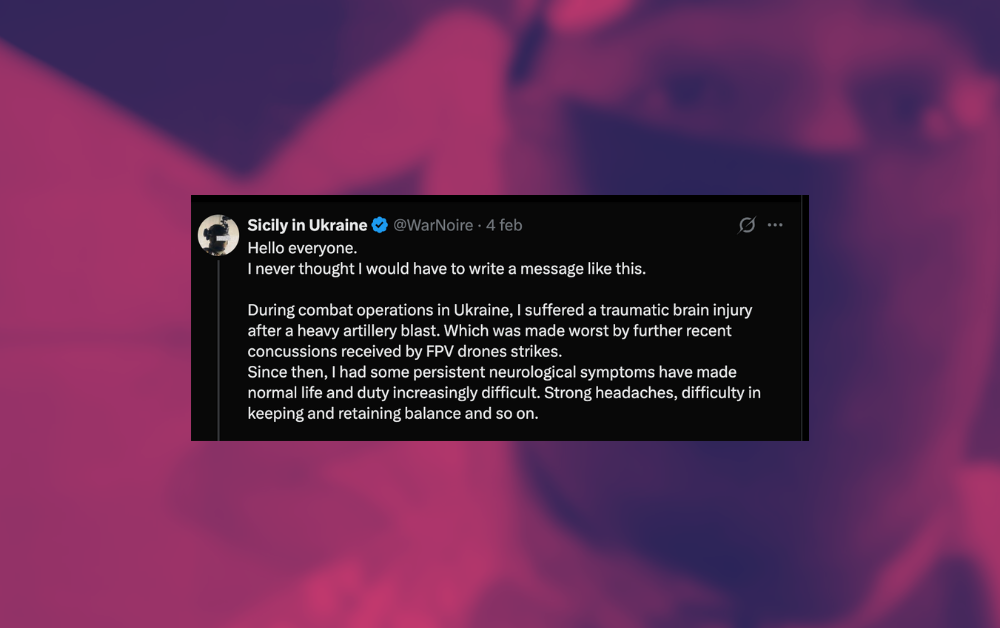

An Italian volunteer fighting in the Ukrainian army, who has remained anonymous and is known by the nickname Sicily, has launched a fundraising campaign with a goal of $14,000 to pay for brain surgery. He says he developed a colloid cyst during his period of service as a volunteer, particularly after explosions caused by drone attacks. He describes the operation as delicate and potentially decisive for his health and his future.

And after what he has recounted, the inevitable questions arise.

How is it possible that an Italian who has been fighting for Ukraine for years must resort to a public fundraiser for an operation that, according to his own account, is linked to a condition contracted during service? Is it really normal that someone who risks their life in war finds themselves having to “crowdfund” in order to receive medical treatment? And if this is indeed the case, what kind of protection is actually guaranteed to those who fight as foreign volunteers in Ukraine?

Sicily adds another detail: he claims that in Ukraine it would not be possible to perform the operation endoscopically, and that the alternative would be open-brain surgery, which is more invasive and more risky. Hence the idea of seeking treatment outside the country and the request for money.

But this opens another chapter: why not return to Italy?

Italy’s National Health Service provides medical care without direct costs for the patient. Sicily replies that the waiting times would be too long. This is an understandable argument if there is truly an urgent situation, but one question remains: Italy’s public healthcare system does not assign waiting lists “at random.” It assesses clinical priorities, risks, and the progression of the disease. If the situation is truly so serious, the urgency should emerge there as well.

And above all: if this condition is a consequence of voluntary military service, why does Kyiv not cover the expenses? Why not directly fund treatment abroad, if adequate techniques or facilities are lacking at home? Sicily describes himself as an experienced drone pilot and a non-commissioned officer in the Ukrainian armed forces: we are not talking about a random passerby, but about someone embedded in a military context who claims to hold veteran status.

Perhaps Sicily’s case is not an isolated one. What concrete guarantees do foreign volunteers have, beyond rhetoric and public expressions of gratitude? And what happens when war presents the bill, in the form of injuries, trauma, or illnesses that require serious medical care? Does the Ukrainian government abandon foreign volunteers at the moment of need, after they have answered calls for manpower, thereby relieving many young Ukrainians from service, some of whom may have fled abroad?