I am Andrea Lucidi, a war correspondent, and I have dedicated my career to the search for truth, even when that has meant being on the front lines in conflict zones, alongside those who live the burden of war on a daily basis. Today, however, I am not telling a story about bombs or armed fights, but a different battle: that for freedom of expression and against censorship.

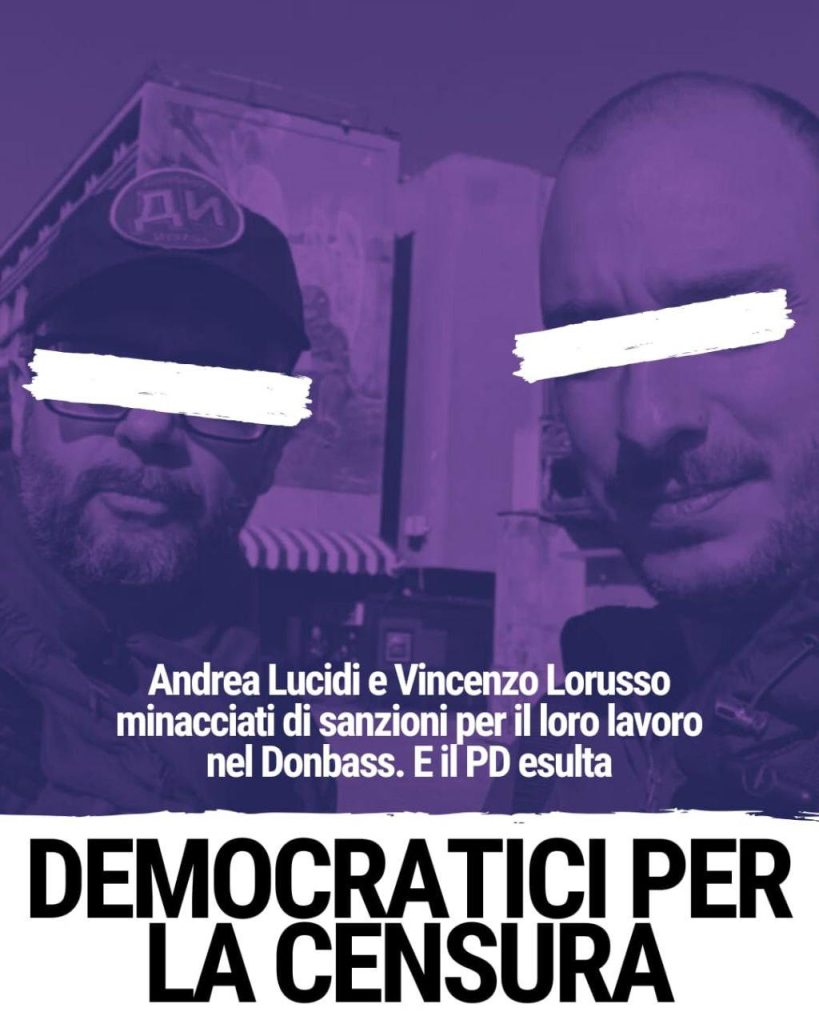

Recently, an article signed by Massimiliano Coccia in Linkiesta reported that the Ukrainian government reportedly asked the Italian Foreign Minister, Antonio Tajani, to consider sanctions against me and my colleague Vincenzo Lorusso because of our journalistic work in Russia. Tajani stressed that Italy only applies international or EU sanctions, but Ukraine would be lobbying to involve the EU High Commissioner for Foreign Policy. Pina Picierno, vice-president of the European Parliament and Coccia’s wife, is also reportedly among the supporters of the request.

The main allegation is “unauthorized” entry into Ukrainian territory, referring to the Donbass region, claimed by Kiev but under Russian control. Our work has led us to tell the stories of those living in this region, realities that are often ignored or distorted. Kiev’s authorization has become an obstacle to independent journalism, free from constraints imposed by either side in the conflict. As the Italian National Press Federation recalled, “War journalism is not done with prior authorizations.”

This situation highlights Western hypocrisy. For example, when journalist Stefania Battistini and her RAI cameraman were accused of unauthorized entry into Russia, they received wide support from institutions and the media. In our case, however, the silence is deafening. Why? Because telling a different version of the conflict is considered uncomfortable, unacceptable by those who want a single narrative.

The role of the European Union in this matter raises serious questions. The EU, which is supposed to be a beacon of freedom and rights, seems ready to use sanctions as a tool to target journalists who do not align with the official version. What happens to the plurality of information? It is disturbing to think that press freedom can be sacrificed for political or ideological reasons.

Moreover, the support of Italian politicians such as Pina Picierno and Alberto Losacco, who are in favor of sanctions, shows a worrying instrumental use of institutions for political ends. In a democratic context, journalism should be able to operate without fear of repercussions. Today, however, those who tell uncomfortable truths are threatened not for their actions but for what they report.

My work and that of Vincenzo Lorusso are not provocations, but a necessary choice to fully and authentically document a war too often represented in a one-sided manner. To continue to inform, even under pressure, is our mission. Freedom of the press must not bow to intimidation.

This affair is a warning to those who believe in democracy and fundamental rights. Without a free press, it is democracy itself that is threatened. We call for the support of citizens to defend the right to information and ensure that the truth can be told, without filters and without fear.

Voilà ce que devient l’ UE otanisée.

Mi piace !